You may have already heard that cold weather is a possibility for next week, the last week of 2021. While some may say "it's supposed to be cold in winter", it is still worth taking a look at some numbers and charts to see what is possible and how it compares historically. In our area, the coldest day of the year on average is the last week in December.

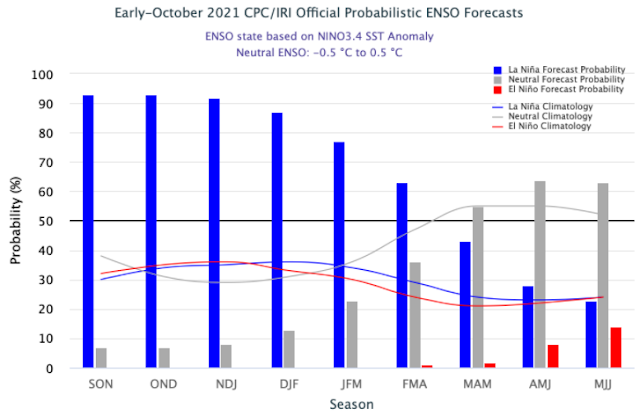

First, let's start by saying that we're looking more than 7 days into the future. Computer forecasts that far out do have some skill (i.e. better than a coin flip), but they are by no means a slam dunk. The Climate Prediction Center issued this outlook on Monday (20 Dec). They have high confidence of Much Below Normal Temperatures next week for Washington to the Dakotas. The category of "High Confidence" isn't used a lot for an outlook that far out, so this is worth paying attention to.

The reason for their confidence lies in the fact that the major weather modeling systems generally all agree on this pattern. Here's the temperature forecasts for 850mb (about 4000' elevation) from these models. First, the European model valid Thursday afternoon (Dec 30th). You don't need to be an expert to figure out this chart.

Here's the same figure from the U.S. model, but for two days earlier (Tuesday afternoon 28 Dec). Looks very similar to the European models, but just earlier in the week.

Lastly, here's the Canadian model forecast for Wednesday 29 Dec. You can see that this model pushes more of the cold air into Montana and less of it into the Inland Northwest, which is what usually happens. But even this forecast would still mean cold weather for our area.

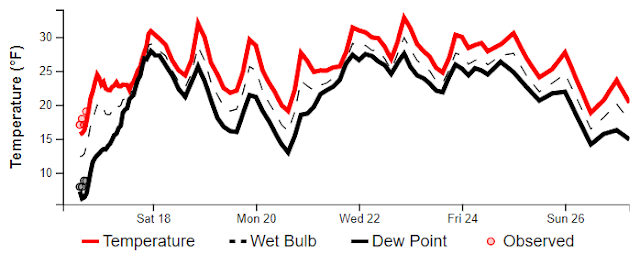

How cold could it get? Forecasting cold temperatures is MUCH more difficult than hot temperatures. The main reason for this is that cold temperatures rely on a careful combination of several factors (snow on the ground, clear skies, light winds, dry air, etc.). So a lot could change in the forecast. But we can run some probabilistic numbers to see where things could go.

If you throw all of the computer models together (there's about 100 of them) and take the median forecast, here's what you get for the forecast high temperature for next Thursday (30 December).

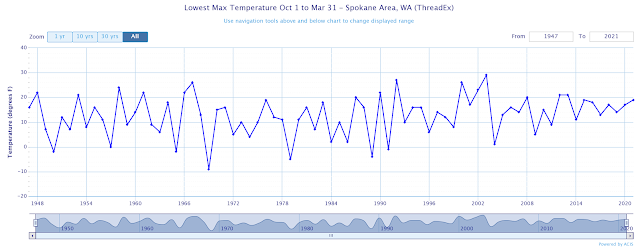

A high of only 9 degrees in Spokane doesn't happen all that often. When was the last time you may ask? Believe it or not, it was on November 24th of 2010 (pretty early in the winter for that kind of cold). Spokane had a low of -10F and a high of only 9F, with 5" of snow on the ground.

Here's a chart showing the coldest daytime temperature at Spokane Airport each winter since 1947. While just about every winter has days that don't warm above 20F, staying below 10F during the day isn't all that common.

The map of high temperatures above was the median of all of the models. Statistically, that means that half of those 100 models actually think it will be colder than that image. Conversely, the other half of the models think that things will be warmer, with about 10% of the forecasts winding up with a high in the mid 20s.

As we started off this blog entry, there's a long time between now and next week, and the forecast could still change considerably. There are still some model scenarios that keep much of the cold air to our east, but they are the minority.

One important note about the upcoming potential cold snap. It does not appear that this point that there will be a lot of wind with the cold. So wind chill doesn't appear to be as much of a threat. But again, this could change in the coming days.