La Nina is here!

After months of a La Nina watch, it finally became official, and we have entered into the realm of La Nina (albeit it a weak one). Ocean temperatures in the key ENSO monitoring region of the tropical Pacific have finally dropped below normal for a period of three consecutive months which makes the declaration official. We've been getting a lot of questions about what this means plus what have we have experienced thus far. So, let's take a deep dive and see what this means for the Inland Northwest.

In a typical La Nina weather scenario, we see cooler and wetter than normal conditions for eastern Washington and north Idaho as the polar jet is typically oriented from the Gulf of Alaska into the Pacific Northwest.

But the typical weather scenario is generally reflective of moderate to strong La Nina episode, and this has not been the case thus far as we've only now reached weak La Nina conditions.

The model consensus moving forward suggests this La Nina will be quite weak and temporally brief. Most of the models suggest we are at the coolest sea-surface temperatures now with subtle warming expected moving forward.

The Winter so far

For those keeping track at home, it's been a very wet winter thus far. So how wet has it been? For the water year (beginning in October) most areas in eastern Washington have seen precipitation amounts above 150% of normal with portions of the Columbia Basin seeing twice the normal amounts. Meanwhile over portions of the Idaho Panhandle conditions have been closer to normal.

From a historical perspective that places much of the region in the top tenth percentile for wetness from Oct-Dec with pockets of record values over central Washington.

From a La Nina perspective that was anticipated, but the temperature portion of the equation has not panned out accordingly. All of the Inland Northwest has experienced a very mild beginning to the winter. Take a look at these temperature departures (most locations are running about 3-5°F above normal)

From a percentile perspective, that places much of the region in the top tenth percentile for this time of year.

Additionally, the coolest temperatures this winter have been anything but winter-like. In Spokane, the coolest temperature reported this winter was 24°F (reported on December 2nd). This is the mildest minimum temperature through January 8th in Spokane since records were kept in 1882.

So, if you combine the very wet conditions with the mild temperatures, what do you get? A general dearth of snow in the valleys, with some significant snow amounts in the mountains (at least the higher ones). In Spokane, we've seen 12.4" of snow thus far which doesn't make the top 10 list for least snowy beginnings to winter (we'd have to have less than 6.2" to achieve that mark).

Of course, not all valleys are seeing a lack of snow, compared to normal, but most are according to this map. Yellow and orange shading equates to below normal snow depth, while blues show above normal snow depth.

If you look closer, you will notice quite a bit of blue over the mountains. Currently all drainage basins over eastern Washington into north Idaho are showing near normal or higher than normal snow water equivalent values (the amount of water contained in the snowpack) for this time of year.

You might ask yourself what's the cause of the warmer and wetter than normal weather thus far. That answer isn't easy to tackle, but if simply examine the prevailing storm track by looking at 500 mb heights (around 18k feet) from November-December it reveals some hints. The longwave ridge axis has been positioned over western Montana this winter which places the Inland Northwest in a predominant west-southwest flow (left image) and favors mild conditions. If we compare this to the storm track in 2022 (right image) which was the last moderate La Nina, we can see significant differences in the storm track. The beginning of that winter showed a longwave ridge displaced over the eastern Pacific which places the Inland Northwest under a cooler west-northwest flow regime. The beginning of that winter was much cooler and snowier than normal.

If we add up the impacts of the temperatures thus far combined with the persistence of snow cover (or lack thereof) this has been an exceptionally mild winter. We can measure the severity of the winter using something called the Accumulated Winter Season Severity Index which takes a look at the intensity and persistence of cold as well as snowfall and the persistence and amount of snow on the ground. When looking at Spokane, here is how we have fared (if you go to the link above you can query other cities in the Inland Northwest) thus far.

The Winter yet to come

The longer-range models continue to suggest we are in for a pattern change in the near future. The longwave ridge axis which persistently been over us or just to our east of us for most of the winter looks like its headed for a significant migration westward. This is called a retrogression. It's just a matter of when it will occur. According to this run (01/09 00z) of the European Ensembles, significantly cooler weather could arrive just before next weekend.

Granted this is just one model run from the EPS, but there has been some run-to-run consistency which gives us a little more confidence in this overall pattern transition.

If we simply look at temperature anomalies associated with this pattern change, it suggests we should see widespread cooler than normal temperatures by next weekend.

And this is expected to continue through at least the end of the month (we only show through the 23rd, but other model data we have access to shows this pattern holding firm).

If you love cold, winter-like temperatures, this offers you some hope. On the other side of the coin, this pattern isn't one terribly conducive to snow, at least not yet. Here's a map of the precipitation departure from normal from 1/16 through 1/23 which shows much drier than normal conditions.

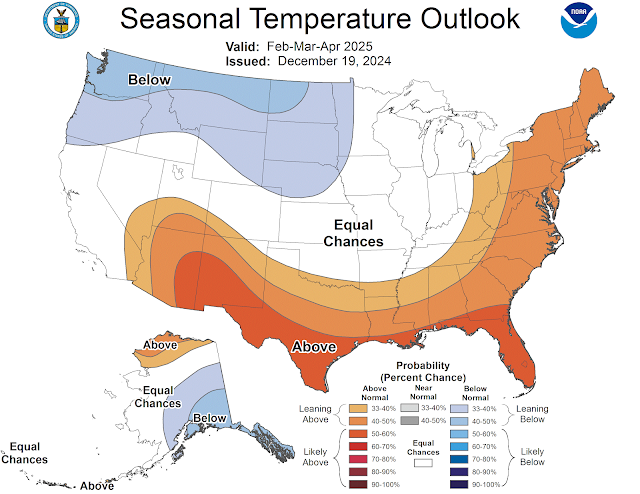

Once we get into February, the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) is still forecasting a colder and wetter than normal period through April, although that forecast was last updated December 19th.

Although the official CPC forecast hasn't been updated since December, it is backed to a certain extent another long-range model, the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). The latest NMME forecast (issued January 7th) is forecasting near normal temperatures and wetter than normal conditions (at least through March).

All this being said, it doesn't guarantee that winter is going to get into full gear in the near future. The long-range models are not infallible, nor are monthly outlooks. However, it looks like things are at least trending away from the very mild conditions we've seen thus far for the winter of 2024-25.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)