Thus far the winter of 2019-20 has been a fairly mild one, in fact since mid-November this has been the mildest winter since 2003 and previous to that the 1967!

|

| Average temperatures 11/15-1/8 by year in Spokane |

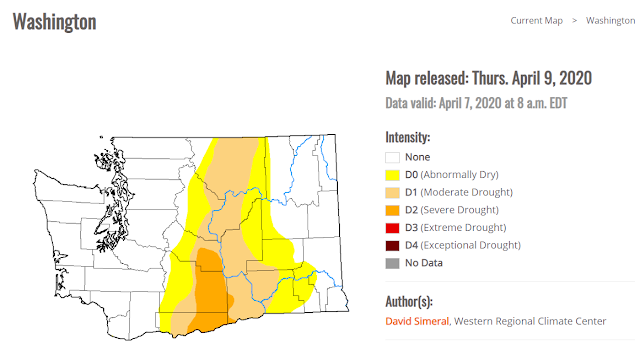

For those that like mild winters this has been a fantastic season, however that often doesn't equate to a good snow pack in the mountains and that has certainly been the case this season. Aside from the northern tip of the Idaho Panhandle, the snow pack this year has been lacking.

|

| Snow Water Equivalent as of 1/9/20 |

But what has been the norm so far this winter is going to come to an abrupt end shortly due to a growing disturbance currently over the Gulf of Alaska. Below on this water vapor loop we can see the system rapidly approaching the Pacific Northwest. This system is the yellow swirl due south of Alaska.

|

| Water Vapor imagery care of College of DuPage |

As the system heads toward the coast it is expected to spin up a deep surface low initially right off the coast and then move it inland through the day. This will spread a swath of precipitation across the Inland Northwest beginning early in the morning near the Cascades and shifting toward the Washington/Idaho border several hours later. The precipitation is expected to be light at the beginning of the event, but then should become moderate to heavy at times in the afternoon as the low gains strength. The depiction below is from the 12z GFS model which is what we trended our forecast toward (as well as several other similar forecasts).

|

| 12z 1/9/20 GFS Run care of Tropical Tidbits |

What is somewhat troubling about the forecast (and the image above) is look how close the rain/snow line (boundary between the green and blue shading) is to Spokane by late afternoon. If the low heads a little farther north than shown here it's conceivable we could see some of the forecast snow turning to rain. This issue is less problematic well north of the Highway 2 corridor in Washington where we are more certain of seeing primarily snow. So how much snow are we forecasting at this time for the Inland Northwest?

|

| Most Likely Snow Forecast |

But if the low moves farther north than expected we might see snow amounts more like this. This is what we call our "Expect at least this much" snowfall

forecast. We expect a 90% chance of seeing at least this much snow.

|

| Expect at least this much Snow Forecast |

So even if the latter forecast pans out, we still would expect to see

some significant impacts to travel across the northern third of

Washington, in the Cascades, and over the Idaho Panhandle.

But

this is just storm #1, we are now expecting another to come in rapidly

on it heels. Once again lets refer to the 12z GFS model from this

morning (1/9/20). Once again the low is forecast to take a similar track

across the Northwest. But what's different about this one is there will

be a much lesser chance of warm air being dragged northward into the

low. And thus whatever falls will likely fall as snow. Also this low

will be a little deeper (and stronger) and thus there will be a greater

potential for more intense snowfall rates and stronger winds.

|

| 12z GFS 1/9/20 Surface low track from Sunday morning-Monday Morning |

So how much snow are we expecting for this second storm? Here is our latest forecast, but this is subject to change.

|

| Sunday-Sunday night Snow forecast |

So between the two systems that's quite a bit of snow. But that's not

the entire story because this snow will likely be followed by a surge

of much colder weather.

Then comes the Cold!

This cold will come care of a building ridge over western Alaska (denoted by red/magenta shading) which will result in the deepening of the trough and resultant northerly flow over western Canada and the Pacific Northwest. The heights will be much lower (and colder) than normal through the period as denoted by the dark blue shading.

|

| 500 mb heights from the GFS for late Sunday through Wednesday |

So

this above is the upper air pattern (at 18k feet above the ground) but

what about closer to the ground? For that let's look at the 850 mb maps

(around 3-4k feet above ground). And this is showing we have some very

chilly temperatures in our future. Pay attention to the loop below and

note the surge of cold blue temperatures heading our way from Monday and

beyond. These will undoubtedly be the chilliest readings so far this

winter, but they could also be some of the coldest temperatures we have

seen in years! Pay specific attention to the blue dotted line on the

chart which denotes the -20°C or colder line. From Tuesday into

Wednesday the model shown below has that line south of Spokane, which is

noteworthy for bringing some of our historically cold temperatures.

|

| 850 mb temperature forecast from the 12z 1/9/20 GFS |

Other

models are aren't quite as cold, but they all share a similar message.

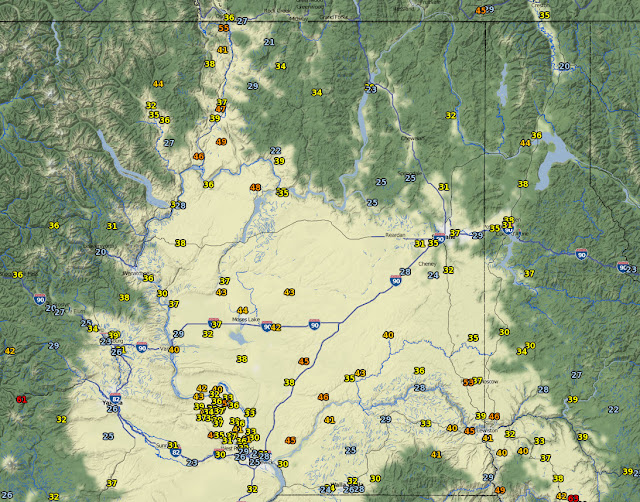

So how cold are we talking? Right now here is our forecast for high

temperatures on Wednesday:

|

| Wednesday High Temperature Forecast |

The

last time we saw a high temperature this cold was on February 5th 2014

when the high was only 11°F. On that day the 850 mb temperature at our

office was right around -20°C. So we are likely looking at temperatures

at least that chilly during the day. For lows we are forecasting even

chillier temperatures with widespread sub-zero readings expected,

including -3°F in Spokane and -15°F in Republic.The Spokane area has not

seen temperatures this cold since 2017.

|

| Wednesday morning Low Temperature Forecast |

But

it could be even colder than is forecast here based on this input from

the GEFS Ensembles. The raw GFS temperatures are denoted by the blue

line on the chart below, while the mean from the GEFS (solid black line)

is at least several degrees colder from Monday-Wednesday. What is more

troubling is there are quite a few of the grey lines (each denotes a

model member) which show significantly colder temperatures than forecast

(yes some are warmer as well). Some of the members for Wednesday

morning are showing readings of -20°F or colder. But most importantly

there is a large spread between all these lines in the Monday-Wednesday

period which suggests there is quite a bit of uncertainty with the

forecast, unlike the first few days of the forecast where the lines are

tightly packed together. So while we are certain, it is going to get

colder, we just aren't sure how cold it will get. There is decent

certainty that conditions will begin to moderate (slowly) after

Wednesday but conditions will certainly remain below freezing.

But there will also be some winds before the cold arrives!

Typical

of an intrusion of cold air from the north, we usually see a period of

brisk north-northeast winds and this system should prove no exception.

We are thinking the winds will arrive after the Sunday system exits the

region or Sunday night into Monday. Again here is the 12z 1/9 run of the

GFS. Notice the blue and green colors that develop after the low dives

to our south. These denote sustained wind speeds of 15 to 25 mph with

gusts from 30-40 mph possible down the Okanogan Valley and Purcell

Trench from (Sandpoint to Coeur d'Alene).

|

| Wind forecast from the 1/9 12z GFS |

Combining the winds and cooling temperatures results in some very cold wind chill values.

|

| Wind Chill Forecast (Min values) for Sunday night-Monday |

So

in summary...if you've enjoyed the mild winter we've seen across the

Inland Northwest thus far, you won't like our upcoming forecast. If you

are yearning to break out your snow blower you will most likely be in

luck with plenty of snow forecast for a large portion of the Inland

Northwest. The snow will be followed by dangerous cold so remember to

protect your pets, pipes, and dress warmly. This weather change may feel

more dramatic than usual since it has been so mild this winter.